Why energy has become the missing pillar of TPM in mobile robotics and automation

For decades, Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) has helped industrial organizations reduce downtime, improve equipment reliability, and embed ownership of assets across operations. The core idea is simple and powerful: maintenance is not a department. It is a system-level responsibility.

Yet as automation accelerates and mobile robots become central to manufacturing, fulfillment, and logistics, TPM is facing a blind spot. Energy is still treated as a background utility rather than as a first-class operational resource.

In 2026, that assumption no longer holds.

TPM today – effective, but incomplete

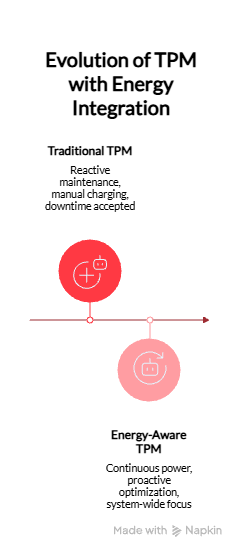

TPM originated in discrete manufacturing environments where equipment was stationary, power was fixed, and failures were mostly mechanical. The classical pillars of TPM – autonomous maintenance, planned maintenance, focused improvement, training, early equipment management, quality maintenance, safety, and office TPM – were designed around that reality.

Modern operations look very different.

Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs), Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs), and pallet shuttles now move continuously across facilities. They are software-driven, data-rich, and energy-dependent in ways traditional assets never were. Downtime is no longer caused only by mechanical failure. It is increasingly driven by energy constraints.

This is where traditional TPM frameworks start to crack.

What TPM means in an energy-constrained, automated world

At its core, TPM aims to maximize Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) by minimizing losses. In mobile robotics, one of the largest hidden losses is energy-related downtime.

Not mechanical failure. Not operator error. Energy.

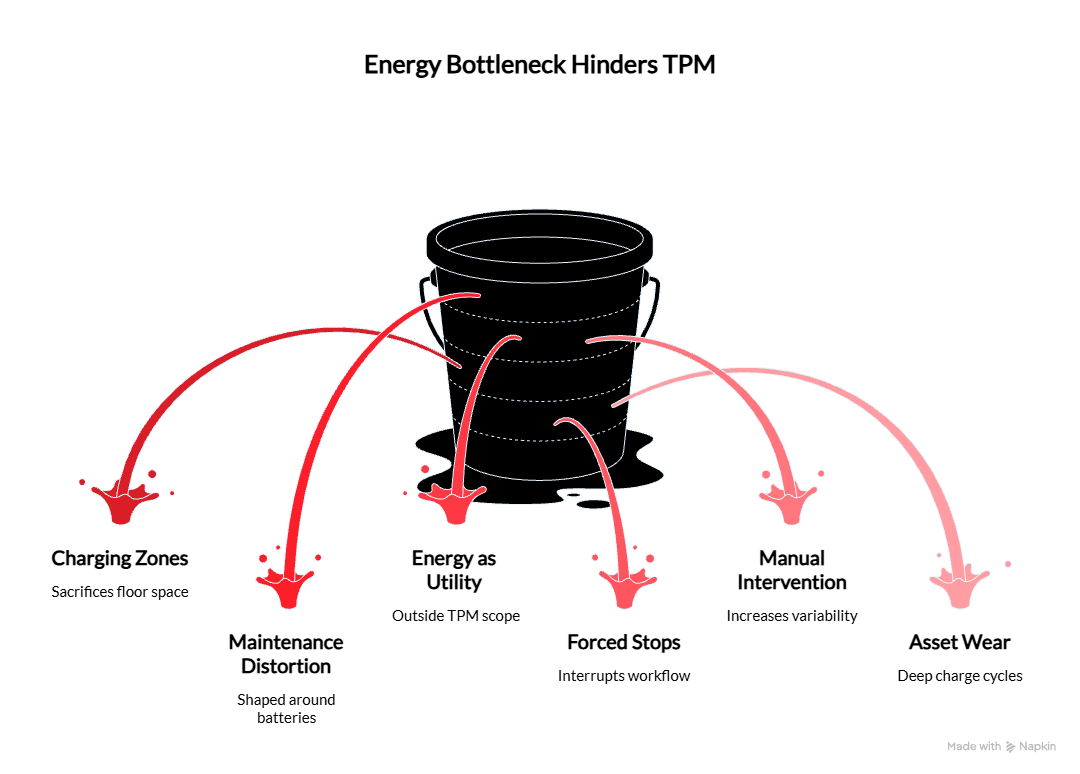

Robots stop to charge. Fleets are over-provisioned to compensate. Floor space is sacrificed for charging zones. Maintenance schedules are shaped around batteries rather than around throughput.

From a TPM perspective, this creates a paradox. You can have perfect preventive maintenance, highly trained teams, and well-optimized workflows – and still accept downtime as inevitable.

Energy becomes the limiting factor that TPM does not explicitly address.

Energy as an operational asset, not a utility

In energy-intensive automated environments, energy behaves like a production resource. It constrains throughput. It shapes asset utilization. It directly impacts cost of ownership and operational resilience.

Treating energy as “outside the scope” of TPM creates a structural gap:

- Equipment availability is capped by charging cycles

- Maintenance planning is distorted by battery degradation

- Continuous improvement initiatives optimize around a fixed energy bottleneck

- Safety and reliability are compromised by aging batteries and manual charging processes

If TPM is about eliminating avoidable losses, energy-related downtime should not be exempt.

The shift from charging to receiving power

One of the most fundamental changes happening in robotics operations is the move away from stationary charging toward in-motion energy transfer.

Traditional charging introduces several TPM anti-patterns:

- Forced stops that interrupt flow

- Manual intervention points that increase variability

- Asset wear driven by deep charge and discharge cycles

- Maintenance tasks that exist solely to support charging infrastructure

By contrast, systems designed to allow robots to receive power while operating fundamentally change how TPM can be applied.

Energy delivery becomes continuous rather than episodic. Downtime is no longer a given. Maintenance shifts from reactive battery management to proactive system-level optimization.

This does not replace TPM. It completes it.

Reframing TPM for mobile robots

When energy is integrated into the TPM mindset, several things change.

Autonomous maintenance expands beyond mechanical checks to include real-time monitoring of energy delivery and consumption patterns.

Planned maintenance is no longer driven by battery lifecycles but by predictable, stable power infrastructure with fewer consumable components.

Focused improvement can target throughput losses previously accepted as structural – such as waiting to charge or routing robots to charging stations.

Early equipment management incorporates energy delivery as part of system design, not as an afterthought bolted onto the floor.

In other words, TPM becomes truly system-wide.

What energy-aware TPM looks like in practice

Energy-aware TPM does not require reinventing the methodology. It requires asking better questions.

Here are eight essential questions energy leaders should be asking when implementing TPM in automated environments:

- How much of our current downtime is directly or indirectly caused by energy constraints?

- How many robots exist in the fleet solely to compensate for charging downtime?

- How much floor space is dedicated to charging rather than production or flow?

- How does energy delivery affect maintenance schedules and asset lifespan?

- What operational risks are introduced by batteries as consumable components?

- How visible is energy performance in our OEE and TPM metrics today?

- Can energy delivery be made continuous rather than interruptive?

- If downtime were no longer energy-driven, what would that unlock operationally?

These are not theoretical questions. They are operational ones.

Why this matters now

The rise of AI-driven automation is increasing utilization, not reducing it. Robots are expected to work longer hours, with higher consistency, and tighter performance margins.

In this environment, energy inefficiency scales faster than mechanical inefficiency.

TPM frameworks that ignore energy as a constraint risk optimizing everything except the bottleneck that matters most.

Conversely, organizations that treat energy as a managed operational resource gain a structural advantage:

- Higher effective uptime per robot

- Lower total cost of ownership

- Reduced maintenance complexity

- Greater resilience under peak demand

This is not about maintenance theory. It is about operational reality.

Where CaPow fits into the TPM conversation

CaPow approaches energy not as a charging problem, but as a power delivery problem.

By enabling mobile robots to receive power while moving, CaPow’s Power-in-Motion technology removes one of the largest sources of accepted downtime in automated operations. This aligns directly with the core goal of TPM: eliminating avoidable losses at the system level.

The result is not just fewer stops. It is a different way of designing, operating, and maintaining robotic fleets.

Energy stops being the exception TPM works around. It becomes part of the system TPM optimizes.

Looking ahead

TPM in 2026 is no longer only about maintenance excellence. It is about operational excellence in a world where automation, energy, and software are inseparable.

The organizations that lead will be those that expand TPM beyond its historical boundaries and treat energy as what it has become: a critical operational infrastructure.

If you are rethinking TPM for modern automation environments, start with the question most frameworks still overlook.

What if downtime was not inevitable?

Want to go deeper?

CaPow regularly explores how energy delivery impacts uptime, cost of ownership, and system-level performance in mobile robotics. Subscribe to the CaPow blog or reach out to continue the conversation.