Over the last decade, “leadership in automation” has mostly referred to which company buys the newest robots, invests in the most advanced software, or deploys the largest fleet.

But if you look closely at how high-volume facilities operate today, these aren’t the indicators that separate the facilities others study from the ones that quietly copy them.

The real dividing line is far more operational and far less glamorous:

Who challenges the constraints everyone else has normalized?

And right now, the constraint shaping robotics more than anything else is energy – not in the abstract sense of “battery tech,” but in the operational sense of how energy availability determines capacity, throughput, failure points, and the physical shape of the facility itself.

This isn’t something operators talk about publicly.

But once you get into working-level conversations, it becomes unavoidable.

Operational energy is the pressure point, not the footnote

Across interviews with operators managing 20 robots, 200 robots, or 300+ robots, the same structural issue keeps surfacing:

their systems were designed around assumptions that don’t age well once the fleet scales.

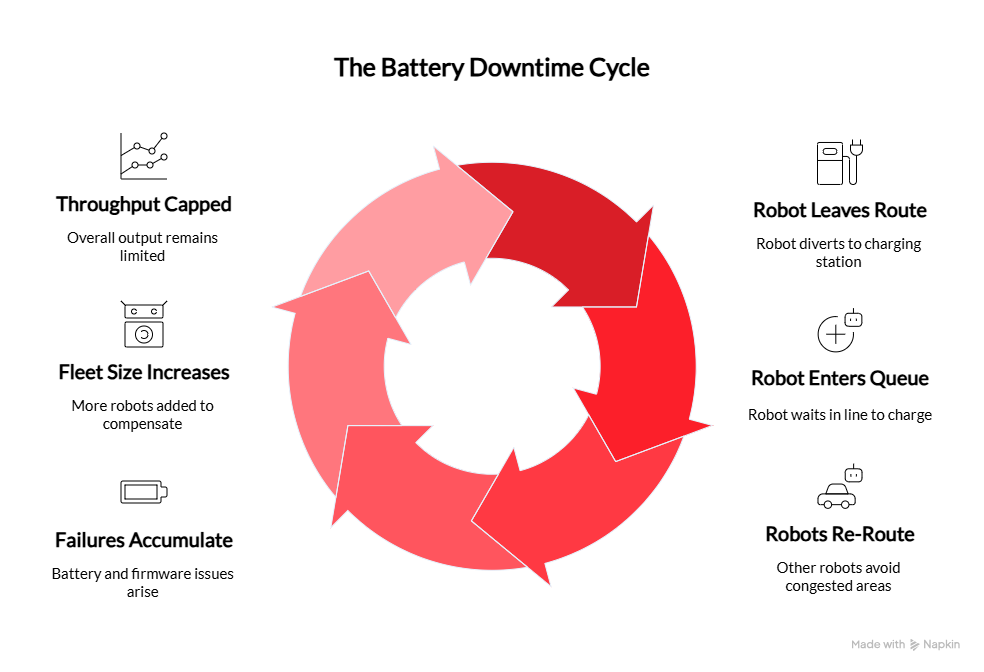

Those assumptions look like this:

- Robots will periodically disappear for charge cycles.

- Fleet uptime will fluctuate based on usage patterns.

- The “extra” floor space needed for chargers is a necessary tradeoff.

- Battery behavior will degrade and must be planned into the model.

- Throughput losses related to energy constraints are simply “how robots work.”

These beliefs are so universal that operators often describe them as physics rather than design choices.

But the moment you ask operators to quantify these assumptions, you see why the industry is hitting structural ceilings.

A few examples that illustrate the gap

These are anonymized, but unchanged in substance.

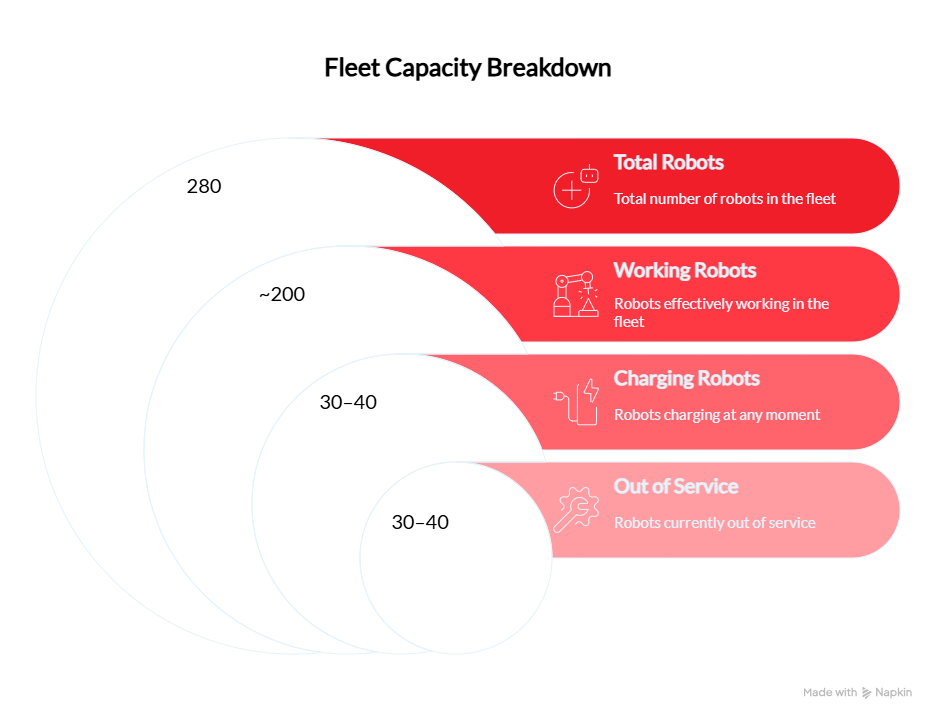

A large ecommerce facility, ~280 mobile robots

On a typical day:

- 30-40 robots are charging at any moment.

- 30-40 robots are out of circulation due to battery faults, firmware issues, board failures, or warranty cycles.

- 50 charging stations occupy square footage that could otherwise support workcells, staging, or aisles.

- When peak volumes hit, orders are reassigned to other sites because the automation system cannot keep pace.

Because that loss has been normalized, the operation is considered “healthy” relative to its peers.

That should concern us.

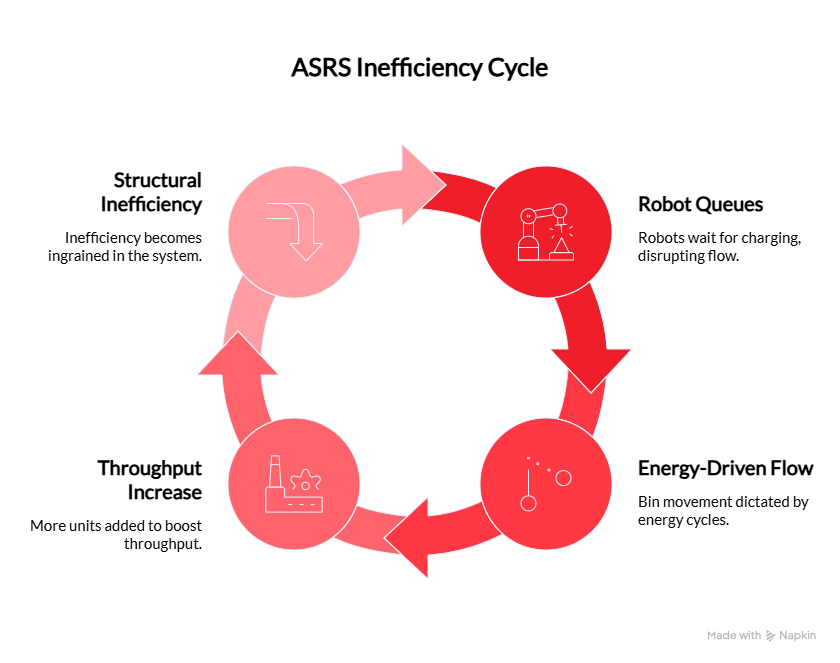

An ASRS site with ~160 shuttles/robots

This site wasn’t presenting a problem; it was presenting a plateau.

When we probed into energy behavior:

- Robots staged in charging queues independent of bin demand.

- Charging logic influenced picking rotations.

- Expansion conversations involved adding more robots, not removing a source of inefficiency.

Again, nothing was broken, which is what makes the inefficiency harder to detect.

An automotive plant running AGCs on a line

Unlike the two examples above, this plant has zero tolerance for delay.

One AGC out of position at the wrong moment has downstream effects.

Their operations lead expressed it clearly:

“If an AGC breaks route or takes a charging detour during a run, we feel it instantly.”

This is the version of energy pressure that exposes itself immediately because takt time leaves no room for background inefficiency.

A 5-robot workcell at a Tier-1 manufacturer

This is the example that breaks the pattern, because it demonstrates what happens when a site stops accepting the usual tradeoffs.

Before the change:

- Out of 5 robots, 1 was always charging, creating a fixed 20% loss.

- The rest ran predictable loops, but always with a missing unit.

- Operators had adjusted staffing patterns around the gap.

After introducing in-motion energy transfer along the queue where robots naturally dwell:

- All 5 units were active at all times.

- No chargers were used for 15 months.

- The facility measured a 2% improvement in total production yield.

- That translated into meaningful financial impact because the plant generates more than $1B in monthly output.

- The installation paid for itself within 12 months.

This is not a story about a “better charger.”

It’s an example of how long-standing energy assumptions distort operational design and how quickly the economics shift once those assumptions are removed.

Why this matters more broadly

These examples highlight a structural truth:

The industry is still building automation strategies around energy limitations that no longer need to exist.

And when one facility demonstrates that a chronic constraint is removable, the effect isn’t inspirational.

It’s mechanical.

Other operators change course, quietly, because they see a working model that contradicts their baseline assumptions.

This is where the “leader or follower” distinction becomes meaningful, not as branding but as operational behavior.

A follower accepts inherited constraints because multiple facilities exhibit the same symptoms.

A leader is simply the first operator who says:

“If this loss isn’t intrinsic, we shouldn’t design around it.”

That’s it.

No slogans required.

Why energy has become the test case

Every industry cycle has one constraint that reveals the difference between structural progress and superficial progress.

In robotics today, that constraint is energy for three reasons:

- Scale exposes the weakness.

A 20-robot fleet can mask energy inefficiency.

A 280-robot fleet cannot.

- Floor space is becoming expensive.

Charging islands turn into silent capacity killers.

- Process stability is compromised.

When robots leave the route, everything downstream reorganizes itself around that absence – even if operators don’t articulate it that way.

So when a site eliminates the need for route deviations entirely, the entire mental model changes.

This is why operators benchmark horizontally.

This is why integrators ask operators what they’re seeing across deployments.

This is why one “unusual” success case can reset expectations across a whole region.

A more grounded definition of leadership in automation

Leadership has nothing to do with:

- being first to adopt a specific brand

- boasting fleet size

- adding more robots than neighboring facilities

- publicizing “innovation initiatives”

Those are outputs.

Leadership in automation, the kind other operators actually learn from, happens when a single site:

- removes a constraint others still treat as fixed

- exposes a flawed assumption through results, not messaging

- demonstrates a stable alternative model

- forces integrators and OEMs to update their own design logic

- becomes the reference call other facilities make quietly

In other words:

Leadership is the first operator who proves something everyone else considered normal wasn’t actually necessary.

Followers aren’t less capable.

They simply update their systems after someone else shows a working precedent.

There is nothing philosophical about it.

It’s operational.

The real question for operators right now

If there’s one question that determines which side of this line an operation sits on, it’s not:

“Are we innovative?”

A more precise question would be:

“Which parts of our model are built around constraints we’ve never actually challenged?”

For many sites, the answer is energy.

Not because they ignored it,

but because they assumed it was unchangeable.

The moment one operator disproves that assumption, the rest of the industry adjusts.

That’s how leadership works here – with consequences that spread much faster than most people expect.